The Who: Finding key sources in the existing literature

So far in this series we have examined how to define a research project – The What, how to construct an effective writing environment – The Where, and what it takes to set realistic timeframes for your research – The When. In this article, we will explore The Who: Finding key sources in the existing literature.

Q1: What methods do you use to identify key sources in existing literature?

According to an online guide of Literature Review Basics from the Wilson Library at the University of La Verne, focus should be on both primary and secondary sources for the research topic. Specifically, the guide states, “When reviewing the literature, be sure to include major works as well as studies that respond to major works.”

Eric Schmieder echoed this thought in his response during the TweetChat event, stating, “When reading existing literature, items in the works cited list that appear multiple times in the article itself or are directly quoted often become key to that article and may be key to my research (assuming the main article is)”. In this way, the sources found during the research efforts may lead you to additional sources relevant to your research.

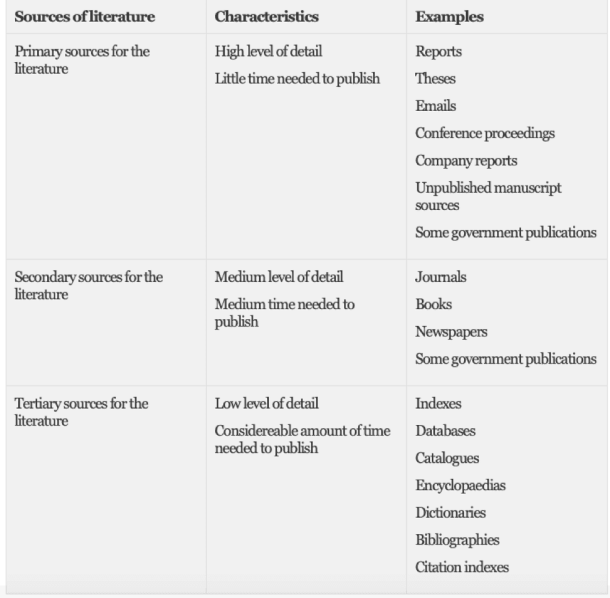

Research Methodology, an educational portal developed by John Dudovskiy, divides literature review sources into three categories as shown below.

Q1a: How do you determine a source to be “key” to your research?

An online guide from the UC Santa Cruz University Library reminds us “Just being in print or available via the Internet doesn’t guarantee that something is accurate or good research. When searching the Web, it’s important to critically evaluate your search results.” To do so they offer three ways to evaluate your results, as follows:

- Look for articles published in scholarly journals

- Look for materials at Web sites that focus on scholarly resources

- Compare several opinions

Schmieder stated, “If the source adds historical knowledge, methodology guidance, or justification for future research that pertains to my current study, it is ‘key’ to my research”.

According to the UNC Health Services Library’s Research Steps, “You don’t have to agree with a source for it to be a key source.” They further suggest using a variety of key sources in your research like:

- one source that provides a good overview

- two sources with sharply contrasting views

- one source for technical information

- one source that concentrates on social implications

As you examine the sources encountered through your research efforts, the University of Minnesota’s Strategies for Gathering Reliable Information resource advises “To weed through your stack of books and articles, skim their contents. Read quickly with your research questions and subtopics in mind.”

They further provide the helpful tips for skimming books and articles shown below.

Q2: How can you use the bibliographies from the articles you reference to identify key sources?

Schmieder noted during the TweetChat event that “If the current article is relevant, those items listed in its bibliography are potentially relevant as sources for the one I have found and am reading.”

The Hunter College Libraries expand upon this topic in their online resource titled Using Good Sources to Find More Good Sources. They state, “We don’t just read sources to find material for our papers. Good sources also lead us to new questions and new sources.” To accomplish that, they suggest ways to use the current source’s keywords, questions, and bibliography for further exploration of a subject.

In an Oxford University Press blog article, Alice Northover offers “Ten ways to use a bibliography”, including:

- Make research more efficient

- Separate reliable, peer-reviewed sources from unreliable or out-of-date

- Establish classic, foundational works in a field

Q2a: Does the frequency of occurrence in other bibliographies identify a source as key to your research?

Schmieder says, “Not necessarily, but if multiple relevant sources cite the same article, it’s likely a key connection and worth reading to consider as a key source for my current research.”

The Searching Cited References guide from CSU Northridge Oviatt Library says that “locating cited references is useful for finding current articles on a topic, identifying the top researchers in a field, and for tenure decisions.” They also share search tips for specific databases including EbscoHost, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR.

Q3: What is citation analysis and how can it help identify key sources?

According to the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) University Library resource, Measuring Your Impact: Impact Factor, Citation Analysis, and other Metrics: Citation Analysis, “Citation analysis involves counting the number of times an article is cited by other works to measure the impact of a publication or author. The caveat however, there is no single citation analysis tools that collects all publications and their cited references.”

Nevertheless, citation analysis is useful and the University of Michigan Library’s Research Impact Metrics: Citation Analysis resource guide offers three reasons for using it.

- To find out how much impact a particular article has had by showing which authors based some work upon it or cited it as an example within their own papers.

- To find out more about a field or topic; i.e. by reading the papers that cite a seminal work in that area.

- To determine how much impact a particular author has had by looking at the number of times his/her work has been cited by others.

During the TweetChat event, Schmieder shared, “Although it provides a general “popularity” aspect that can be interpreted as a relevance score, I evaluate the source independently for my own use and relevance/value.”

The University of Cincinnati provides a resource on Citation Analysis Tools & Instructions to introduce “the sources available to the UC community for creating citation counts and conducting citation analysis and explain their coverage and method of searching.” This resource includes details on Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Altmetrics.

Q4: What is journal impact factor and what role does it play in identifying key sources?

The UIC University Library guide on Journal Impact Factor (IF) states, “The impact factor (IF) is a measure of the frequency with which the average article in a journal has been cited in a particular year. It is used to measure the importance or rank of a journal by calculating the times it’s articles are cited.”

Schmieder said, “JIF identifies the practical use and citation of articles published within a journal. This again can imply relevance and value, but is less substantial IMO to the value the source has on my research. The benefit to using articles with high JIF is later association.”

Clarivate Analytics notes, “Though not a strict mathematical average, the Journal Impact Factor provides a functional approximation of the mean citation rate per citable item.” Further, “The Journal Impact Factor is a publication-level metric. It does not apply to individual papers or subgroups of papers that appeared in the publication. Additionally, it does not apply to authors of papers, research groups, institutions, or universities.”

Q5: In what ways do key sources impact your research efforts or results?

According to the Study.com lesson titled Evaluating Sources for Reliability, Credibility, and Worth, “Before you evaluate your source, you need to first evaluate the purpose of your research. If you are researching for an academic paper, then you need to have very credible, reliable, and worthwhile sources because your teacher or professor will be judging the authenticity of the sources. However, if you are perusing the Internet for general interest, then you are left to your own judgment of the information.”

The CRAAP Test is discussed in the online guide from the UC Santa Cruz University (referenced earlier) is an effective method for evaluating the quality of research sources:

- Currency – the timeliness of the information

- Reliability – the importance of the information

- Authority – the source of the information

- Accuracy – the reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the information

- Purpose – the reason the information exists

Q5a: How can key sources be used to focus your research project?

Sandra Jamieson at Drew University published an online resource for writers titled “Drafting & refocusing your paper” in which she addresses this topic directly. She says, “You’ve chosen a topic, asked questions about it, and located, read, and annotated pertinent sources. Now you need to refocus your topic. What changes do you need to make in order to account for the available sources?”

Continuing on, Jamieson notes that “Once the topic has been refined sufficiently for the research to begin, the student gradually formed an opinion on the subject, answered the research questions, and refined the topic into a thesis”. It is through the research process that the specific research topic and related questions become clear.

Q6: How can you improve your potential of writing articles that become key sources for future research by others?

By focusing effort on increasing one’s h-index, a researcher can improve their potential of becoming a key source for the research of others. According to the UIC University Library Citation Analysis guide referenced earlier, “The h-index is an index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output [and] attempts to measure both the scientific productivity and the apparent scientific impact of a scientist.”

Interested in increasing your h-index? A paper by Gola Dem titled “How to Increase Your Papers Citation and H Index” shares the following five steps used by Nelson Tansu, the youngest professor in Indonesia, to increase your citation index.

- Self citation and more self citation

- Double publication

- Rapid self citation

- Go to SPIE Conference

- Quote more references and cover up your act, the important is the number of self citation

Obviously the final suggestions proposed by the last referenced article are a bit tongue-in-cheek as we finish out the discussion of key sources in the literature and reliable sources. The point, however, is to be careful what you use for references to ensure that the quality of your work does not come under unwarranted scrutiny.

Please note that all content on this site is copyrighted by the Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Individual articles may be reposted and/or printed in non-commercial publications provided you include the byline (if applicable), the entire article without alterations, and this copyright notice: “© 2024, Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Originally published on the TAA Blog, Abstract on [Date, Issue, Number].” A copy of the issue in which the article is reprinted, or a link to the blog or online site, should be mailed to Kim Pawlak P.O. Box 337, Cochrane, WI 54622 or Kim.Pawlak @taaonline.net.