Reflect and reboot

In my part of the world, the days are short and bright, and the nights are long and dark. Without the screen of leaves, without colors from leaves and flowers, the brilliant blue sky draws my attention. Along with these seasonal changes, we can’t help but notice that we’re on the last page of the calendar. This is a time for reflection.

Let’s face it, in the pre-smartphone days we had small reflective moments now fractured by sound bites and fragments of news or photos of elementary school friends’ new babies. How can we pull away long enough to reconsider the proverbial big picture?

John Dewey saw reflection is important to learning, and essential to the process of discerning our moral aims and goals. observed that we must seriously ask by what purposes we should conduct our conduct, and why we should do so; what it is that makes our purposes good (Dewey, 1939). If we are trying to teach, write, and work for individual and social good, how do we know it is good unless we take the time to reflect on our underlying values? Dewey defined the function of reflective thought: “to transform a situation in which there is experienced obscurity, doubt, conflict, disturbance of some sort, into a situation that is clear, coherent, settled, harmonious” (Dewey, 1939, p. 851). Peltier et al (2005) pointed to two interrelated ideas in Dewey’s writings about reflection: first, a state of doubt, hesitation, perplexity, mental difficulty, in which thinking originates, and second, an act of searching, hunting, inquiring, to find material that will resolve the doubt, settle and dispose of the perplexity” (Dewey, 1933, p. 12).

Beyond reflecting on problems and ways to find a clear and coherent approaches to dealing with them, researchers also define reflection as a process of retrospectively examining experience to gain awareness, understanding, and appreciation (Roessger, 2014). Guillaumier (2016) discusses reflection as essential to creativity and creative thinking: “creativity is rooted in reflection and vice versa… Perhaps the main prerequisite for understanding and practising both reflection and critical thinking is curiosity and an open mind” (p. 356-357).

Lest you think about reflection as fuzzy navel-gazing, here are three approaches to help you find practices you can use. First, consider the nonreflection-reflection continuum created by Peltier, Hay, and Drago (2005).

(Peltier, Hay, & Drago, 2005, p. 253)

Using this continuum as a conceptual framework, we might ask ourselves: What might help me to move from understanding to deep learning? What “personal beliefs” about my work as a writer, my relationships to underlying research and the content I write about, or the people I write for, might I call into question?

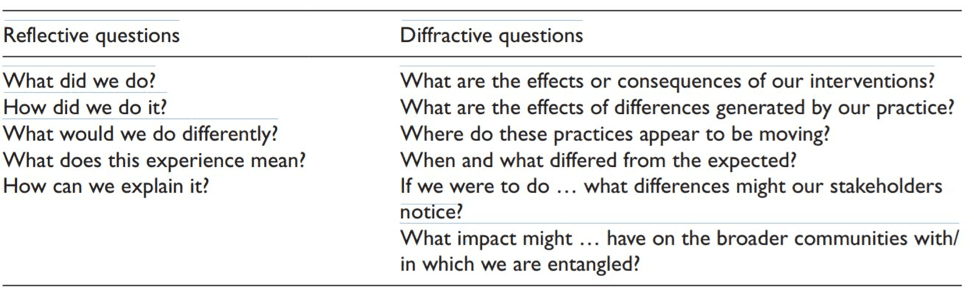

The second approach is drawn from Keevers and Treleaven (2011). They write about organizations, but the principles can apply to us as individual writers. They distinguish between reflectionand what they call diffraction. “Diffractive practices afford opportunities to attend to and critically evaluate the effects of differences, interferences and exclusions” generated by the work at hand) (Keevers & Treleaven, 2011, p. 509). Here are some questions they identified:

(Keevers & Treleaven, 2011, p. 509)

By asking the kinds of questions Keevers and Treleaven outlined, we can reflect not only on what we think and feel about our own writing, but also on how it relates to the world. Did it have the effect we’d hoped to accomplish? What impact did it make?

I can hear your rumblings already: I don’t have time! I am busy! If these were your responses, you might want to look at the classic by Donald Schon: The Reflective Practitioner (Schon, 1983). Schon talks about “reflection-in-action,” that is, the ability to “reflect on knowing in practice” which can serve as a corrective. He observes that “through reflection, practitioners can surface and criticize tacit understandings that have grown up around the repetitive experiences of the specialized practice, and can make new sense of the situations of uncertainty or uniqueness which they may allow themselves to experience” (p. 61). From this angle, might internalize some of the questions to ponder on an ongoing basis.

When you are working on a computer or device, and you want to load new software, you’ll need to restart the computer. The computer just won’t work properly if you don’t. If you want to take a fresh perspective on stalled or unsuccessful projects in the new year, if you want to work towards new goals, or you might need to restart and “install” new modes of thinking and doing.

This year I am going to walk the talk. I am going to unplug from academic writing, and take some time to do things that feed my creativity and imagination, including looking at the sky, painting and art journaling, a road trip in the beautiful Southwest, reading literary fiction, and being with people I love. When I write my January Abstract post, I will let you know what this reflective time meant to my vocation as an academic writer and goals for the new year. I hope you will share your own reflective experiences and your inspirations for a new year.

References

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the education process. Boston.

Dewey, J. (1939). The moral situation. In J. Ratner (Ed.), Intelligence in the modern world. New York: Random House.

Keevers, L., & Treleaven, L. (2011). Organizing practices of reflection: A practice-based study. Management Learning, 42(5), 505-520. doi:10.1177/1350507610391592

Peltier, J. W., Hay, A., & Drago, W. (2005). The reflective learning continuum: Reflecting on reflection. Journal of Marketing Education, 27(3), 250-263.

Roessger, K. M. (2014). The effects of reflective activities on skill adaptation in a work-related instrumental learning setting. Adult Education Quarterly, 64(4), 323-344. doi:10.1177/0741713614539992

Schon, D. A. (1983). The Reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Harper Books.

Janet Salmons is an independent scholar and writer through Vision2Lead. She is the Methods Guru for SAGE Publications blog community, Methodspace, and the author of six textbooks. Current books are the forthcoming Learning to Collaborate, Collaborating to Learn from Stylus, and Doing Qualitative Research Online (2016) from SAGE.

Janet Salmons is an independent scholar and writer through Vision2Lead. She is the Methods Guru for SAGE Publications blog community, Methodspace, and the author of six textbooks. Current books are the forthcoming Learning to Collaborate, Collaborating to Learn from Stylus, and Doing Qualitative Research Online (2016) from SAGE.

Please note that all content on this site is copyrighted by the Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Individual articles may be reposted and/or printed in non-commercial publications provided you include the byline (if applicable), the entire article without alterations, and this copyright notice: “© 2024, Textbook & Academic Authors Association (TAA). Originally published on the TAA Blog, Abstract on [Date, Issue, Number].” A copy of the issue in which the article is reprinted, or a link to the blog or online site, should be mailed to Kim Pawlak P.O. Box 337, Cochrane, WI 54622 or Kim.Pawlak @taaonline.net.